“Follow your dreams” is perhaps the most ubiquitous inspirational directive of all time. As Psychology Today once pointed out, the phrase “encourages us not to stay content in our safe existence, but to make a leap, to follow the passion that would drive us if we just gave it the chance.” But the “dreams” to be followed here are essentially desires — not the often-bizarre visions that color our sleeping lives. Following actual dreams is an entirely different beast, an adventurous practice that’s taken shape in a wild assortment of real-world creations — from the sewing machine and the periodic table to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory.

Los Angeles native Sacha Chambers falls into that brave category of people who trusted their subconscious minds and set out to realize an actual dream. “I had a really trippy dream one night,” Chambers recalled. “Like a really, really, really trippy dream. All I could really remember about it was that it was hot and there was a kind of amorphous, glowing substance … I did not know what it was. When I woke up in the morning, my first instinct was: I would like to blow glass.”

Save for some theater experience (including costume and lighting design), Chambers had “no art background whatsoever” and had “never actually seen glassblowing.” Nevertheless, she embarked on a weeks-long, pre-internet scavenger hunt for a glass studio willing to show her the ropes. Combing through the Yellow Pages, she started calling every glass-related businesses with a pitch that went something like, “Hey this is the deal: I had a dream and I want to blow glass.” After a lot of hang-ups, Chambers came across Los Angeles glassblower John Gerletti and explained her conundrum: “I said, ‘OK, look, I’ve been doing this for weeks. I had this dream [and] I want to learn how to blow glass. Do you know anything about it? Can you help me out?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, I blow glass and I love dreams! Why don’t you come on down?’ And it turned out that his studio was like five minutes from my house. So he ended up taking me on as an apprentice and I was there for about a year before I then discovered a scholarship opportunity to go study at Penland School of Craft in North Carolina.”

During a beginner’s course at Penland, Chambers traveled to Corning, New York, to attend the Glass Art Association’s annual conference. While there, she visited with reps from various art schools and got the best vibe from the small Canadian school Espace Verre. “I met all of these [Espace Verre students] and they were the coolest — the most down-home, real artists … hanging out in the fields and blowing fire and hula hooping and talking about glass — no pretense, no stuffiness whatsoever. So I decided that that was the school I was going to go to.”

With the same determination that led her to glassblowing, Chambers traveled to Montreal to visit Espace Verre, which is part of a public college system typically only open to residents of Quebec. “Without speaking French or having any real plan, I just left and went there and saw the school,” she explained. “And they were like, ‘Well, this is kind of unorthodox. You’re not Canadian … and you don’t speak French. This program is in French.’ And I was like, ‘Don’t worry about me … I’ve got this.’ I sold my car and my belongings and I packed myself up and I showed up on the first day of school as promised. They were kind of shocked … But they took me.”

After jumping through a few strategic hoops to enroll at Espace Verre, Chambers realized she needed to learn French tout de suite. “I realized quickly after getting there that I had maybe pushed the boat out a little far,” she said. “I spent the first year and a half as a student like a mime. But when things are on fire and sharp, that’s a real motivating factor to learn a new language. So I quickly learned glassblowing French.” As for basic vocabulary, Chambers took a cue from The Color Purple and labeled everyday objects in her apartment — essentially teaching herself French the way Nettie taught her sister Celie to read. “So that’s how I learned French,” Chambers said. “I taught myself like Miss Celie. I would watch French cartoons and I would listen to French radio. I just forced myself to be as immersed in it as I possibly could. Because in Montreal actually you can escape. You can go and live in the English part of town and you don’t ever have to learn French. That wasn’t going to be an option for me as a student [or] in terms of making friends. Because the Quebecois people don’t appreciate that vibe at all … After two years, all of a sudden I was able to speak … and [by] my final year in school, I was the class representative and [laughs] going to talk to the director to lobby for projects for my class — in French.”

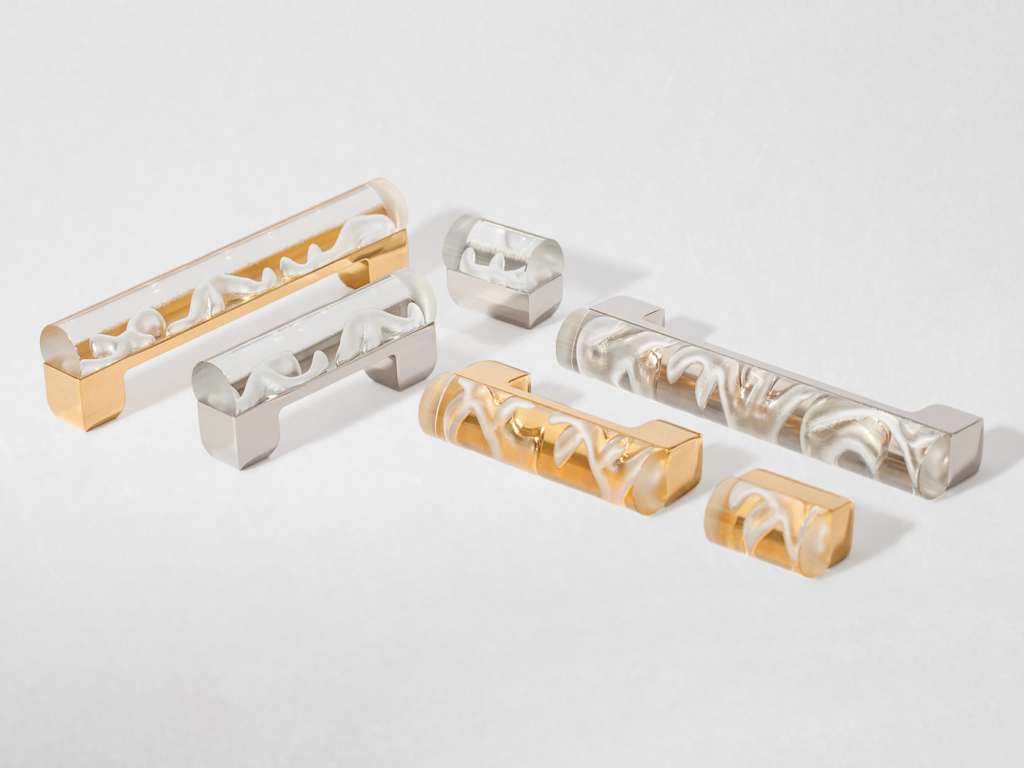

After spending seven years in Montreal and obtaining Canadian residency, Chambers returned to Los Angeles and her glass art began to evolve. Feeling disenchanted by the limited possibilities of the complicated, high-concept work she developed at Espace Verre, Chambers shifted gears to start focusing on functional glass art — an evolution fueled by a partnership with revered interior designer Nancy Corzine. After years of working with Corzine, Chambers set out on her own to launch (gl)aesthete — an exquisite line of cabinet hardware named after a fusion of the words “glass” and “aesthete.” As (gl)aesthete is the latest addition to the Alexander Marchant family, we reached out to Chambers to learn more about her fascinating story, her burgeoning brand and what else her dreams might hold.

I’ve watched a few glass artists at work and it looks pretty dangerous.

It is. Funny enough though, I’ve had a lot of different careers and made different job moves in my life. I’ve burned myself a good number of times in the hot shop — that’s kind of a job hazard — but the worst injuries I’ve ever taken have been from doing things like bartending. Luckily, I haven’t seriously injured myself glassblowing.

What was your work like when you were studying at Espace Verre?

It was very, very complicated. I had a lot of big ideas with the things that I wanted to do in glass and most of them defied science and gravity. I was obsessed with trying to make glass float. I would do very, very large — upwards of 100 pieces – hanging installations. I did this one thing that looked as if water had collected in a ceiling and broke through — and you snapped a photo of that as it broke through the ceiling. It was comprised of around 90 pieces of glass varying in size from three inches to three feet in length. I don’t know if you’ve ever gone to a glassblowing studio and seen them drop what looks like a raindrop — they’re called Prince Rupert’s drops. They just drop a blob of glass off the end of a punty into a bucket of water and it’s just a perfect little teardrop, or raindrop, shape. And because it’s gone into the water, it’s tempered. So I had figured out a way to split that shape in two so that it was a mirror image of itself. So you couldn’t really tell which way the water was going — whether it was it dropping up or dropping down. So I had made like 90 of those and [installed them as though they were] coming out of the ceiling. It took maybe four or five months to make — and maybe 30 hours to install [laughs]. It was so intense! The installation process of it was so intense they actually left it there when I moved back to Los Angeles. They kept it in their conference room. They liked it but they were also like, “We’re not going to try to uninstall this.” So I did a lot of large-scale installations … My very first project that I attempted in my first year of school — bless my little heart — was that I wanted to make a set of matryoshka dolls in glass. Yeah, that never got realized [laughs].

When did your work start to become functional?

[During] my graduate program, I started to actually burn out a little bit. I started to burn out on glass. And I started to have a crisis of conscience. I was starting to understand just what a tax making glass took on the environment. And I was feeling a lot of ways about being a glass artist. And that combined with the fact that glass is a very elitist medium. One of the things that drove me to this school in Montreal was that it was associated with a public college system. These kids could go to glass school, get all of this amazing education, incredible teachers for I think less than $10,000 — for years of school. They would crack me up because they would protest — not that protests are funny these days — but they would protest in the quad of their school because the parking permit would have been increased by $20, making parking on campus go from $40 to $60 for the entire semester. I would hit the ground laughing. I think you have to pay $60 to get a college application out of some of these institutions.

So in the United States, if you don’t have money to access a glass education, that’s not happening. You kind of have to come from money to have ever even been exposed to glass art in the first place. That’s not something you just see all around you. Like you would be exposed to a Dale Chihuly special certainly, but you’re not going to find out about the early days of Yoko Ono. And you’re not going to find out about all of these amazing artists. And so I realized: glass is glass for glass people. You make glass to impress other glass artists. Or you make glass in the hopes that glass collectors catch onto your work and help you continue making glass. And that started to really bum me out. That this incredibly beautiful medium was inaccessible to the majority of people, and the access that they had to it limited their understanding of what went into its creation.

[Someone can] go to Ikea and buy a set of 30 tumblers for $5 and then go to your friend’s shop and [find that] one tumbler costs $85. Why is that? That becomes very hard to justify and defend because they haven’t had exposure to the medium and what all goes into it. It bummed me out that people didn’t have an understanding of it. It bummed me out that friends of mine would make this beautiful work that either would only be seen by glass people or only be seen by collectors and then — worse — be put on a plinth or in a curio cabinet in someone’s home and never be touched. All this amazing texture that they’ve created. All this amazing research, all of this work that they’ve put into [it] is now locked away because it’s precious and it’s fragile. And that really upset me.

And so at the time that I was experiencing this burn out, I started trying to make smaller pieces of glass that could be tactile. I started just playing around with shapes and at some point I stumbled across a spinning top. I had figured out how to — just with my hands — grab a blob of glass and shape it and pull a spinning top out of a blob of glass. So I started making these as gifts for people, including my mom. I had given her one as kind of a little meditation tool to keep on her desk at work. At the time, and for many years, my mom was working for Nancy Corzine, who’s a very, very big designer in the United States and internationally. And she had one of these [tops] on her desk and Nancy came by one day and she saw it and said, “What is that?” And my mom told her it was a thing I had made her. And she said, “If Sacha could alter the shape of that slightly, that would make really great hardware.” And when my mom came back and told me that, a huge light went on and I was like, “Oh my god, I can put glass in people’s hands.” And not in like a cheesy way [but] in a really important way, where I can still play with light, and I can still play with texture, and I can still play with all of the things that I love about glass. This can become a thing that people can experience as opposed to lock away. And that’s how that happened.

Do you use lampworking or glassblowing techniques to create your hardware?

So with the hardware, I don’t actually blow. So there’s a difference between a blowing and lampworking furnace. What I do is solid work for the hardware. So I use a punty, which is a solid rod, to collect the glass … and then go straight to the forming process of using my hands or steel to shape that. So there’s no actual air inclusion in my hardware. Where my handles come into play, those have nothing to do with either lampworking or glassblowing. Those are a completely other technique that I’ve created on my own. So I work with preformed rods that I worked to devise the shape of. I used to make them myself but now I have those parts made for me because I don’t have time to make them all in the quantity that I sell them. So those rods get made and then, in the case of the Pavé or the Codex, I use varying techniques to either chisel or hand-carve away the glass from the inside surface. And then trap the light inside that carving once I mount it on top of the metal hardware.

Hand-chiseling sounds pretty tricky with glass. Is it as delicate as it looks?

Yes [laughs]. I now am at a place where I’m really consistent. I may break one in say 20 or 25. But it is a very laborious, focused, time-consuming task where it is all about maintaining consistent rhythm and pressure through both of my hands as I repetitively tap those spots out of the glass.

Do you have any new collections in the works?

I am hoping to see how the world kind of plays itself out in the next few months and perhaps start collaborating with someone else, and maybe create a new line. But I’m kind of playing with seeing where the world goes right now [and] if there’s still room — which I hope there is — for luxury hardware. Hopefully soon, I’m hoping to create a round version of the Pavé handle as a knob. That’s something I’ve wanted to do for a minute.

Have you made any creative discoveries during quarantine?

I’ll be honest: I also teach pilates at this point in time. So I’ve been spending most of my quarantine deepening that knowledge. I was drawn to pilates in a way that is kind of glass-related in that it’s about efficiency of movement. So in working on my alignment in my joints, I have a deeper understanding of how to be more relaxed when I do something like the Pavé. How to be more in charge of adding control of my joints and my body. Making glass can be quite taxing. So that’s been an exciting discovery — more controlled motion within my own body. But more than that, honestly, within the state of the world, just being able to kind of take a step back and say, “This is important but there’s a lot of other things that are super-important too. So the kind of intensity that I could potentially bring into the studio has been tempered. And there’s a deeper appreciation for time as it has been moving so strangely.

So let’s say things become a little more normal. What would you say are your hopes for (gl)aesthete? Are there things you want to introduce that we’re not seeing yet?

My hopes are to create work that is even a little more accessible. So maybe [pieces that are] less time-consuming and less laborious so they can reach a wider audience without sacrificing what it is that I love about the material.